REMEMBERING – REMINISCING

An Art Project to the 50th Anniversary of the "Cultural Revolution"

眼见 “为实”

文革五十年艺术项目

“FACETTEN DES ERINNERNS”

this project is funded by the free Hanseatic city of Hamburg, cultural authority center.

德国自由汉莎市汉堡资助项目

introduction

It has already been 50 years since "The Unprecedented Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution" was launched in China. Since then, China has changed a lot. However, within the People's Republic there has so far been no in-depth examination of this decisive historical era. However, this circumstance is by no means due to a "historical necessity" but must be seen as the result of a deliberate concealment.

When we remember, we remember primarily in visual images. A multitude of historical images come to us when we think back to that time today. They are images that color our awareness of this era and give it a certain character. In addition, the surviving images from that time are doubtful: they are almost without exception the products of party-directed propaganda. Society and everyday life were primarily determined by political influence. It permeated - whether recognizable or not - all things and almost all areas of people's lives.

Contemporary Chinese art should and must respond to this situation of tradition. For this reason we started this project. We try to counteract the propagandistic photos from that time with images of memory. Like a palimpsest, these images and the propaganda images overlap each other and question each other. As a result, the photos are stripped of their bright propaganda color and become evidence of personal conflict. In this sense, memory is made visible to the viewer in a visual form. Professor Monika Wagner calls this endeavor “re-education of images” in the catalog for this exhibition.

Ni Shaofeng and Deng Huaidong were born in the early 1960s and received their first visual influences during the Cultural Revolution. You are therefore eyewitnesses to this era. In the early 1980s, while they were receiving their university education, China was experiencing a period of relative political détente. It is perhaps these circumstances that have influenced her reflexive attitude.

展览前言

“史无前例的文化大革命”发动已经过去了半个世纪。五十年来中国发生了巨大的变化。然而,对文革的全面彻底的反思仍未展开。这一局面的产生并非“历史的必然”,而应视为有意遮掩的结果。

人们主要是通过图像来进行记忆的。回首往昔,各种历史的图像纷至沓来,规定了我们历史记忆的色彩。而文革流传下来的图像却是那样值得怀疑:它们绝大多数是宣传的产物,那是一个泛政治的时代,政治宣传或隐或现地浸染了人们生活的方方面面。

对此,当代中国视觉艺术应有所回应,这也正是本项目的缘由。两位艺术家尝试以个人记忆与文革历史照片加以对照;在相互掩映,相互质疑中,图像退去宣传性的鲜亮,显露出历史的斑驳。历史的记忆从而转化成为可视可睹的形象——眼见的实在。瓦格纳教授在其为本次展览目录所撰写的文章中,将这种做法称为“图像的再教育”。

本项目的两位画家,倪少峰与邓怀东,出生于六十年代初,在文革中度过了人生的早年,轰轰烈烈的文革构成了他们最初的视觉经验,使他们成为文革的目击者。或许是八十年代初期较为宽松的高校教育,让他们形成了对这段历史反思的态度。

Original

deformation

Interpretation

A group of three Chinese artists working on a joint project. This year marks the fiftieth anniversary of the beginning of the Great Cultural Revolution in China, which started in 1966. For the artists it is a good opportunity to artistically explore the process of memorizing historical events.

The focus lies on memory’s nature, which is then linked to photographic images taken at the historical event. The starting point, therefore, is a selection of 50 widely circulated photos from the time of the Cultural Revolution.

All originals are subjectified by the artists in a three-stage process of alienation and restoration, at the end of which each individual will have created 50 art objects. Everyone doing it in their own way and pace. Those different approaches represent the three different dimensions of memory triggered by photographic images.

The resulting works combined express the memory of a historic event. In particular, they give an impression of the ever changing nature of memory and allow a reflection of one’s own experience on the part of the viewer. That's the guiding concept for this project.

三位中國藝術家的一項聯合創作。肇始於 1966 年的文革,今年適逢五十周年。這三位畫家以此為契機,採用圖像的形式探討與反思歷史事件的記憶過程。本計劃的重心在於由照片引發的歷史記憶。因此,選取了五十幅當年的流行照片作為切入點。三位畫家經由三個步驟對照片進行陌生化處理並加以恢復,最終分別制作出五十幅作品。創作過程中畫家們各自采取了不同的創作方式,以展現由照片所引發記憶的三維特征。作為一個整體,這組作品將多維度地展現文革的記憶;給予觀者記憶本身並不確定的觀感,並提供反思的空間。此即本項目的主導思想。

CONCEPT

The three different procedures of processing the images represent three different modes of memory: the individual memory of the past as shown in a family album, the authorized reconstruction of historic events with the aim of directing the memory in a desired direction, and finally, the diffuse cloud of collective memory. The artists also provide concepts for the exhibition of the three different approaches: the oil painting photos in showcases, the paintings on the walls and the composite ink paintings in a maze of wall screens.

In a catalog the processes behind the forthcoming of these works will be shown and explained.

對圖像的三種處理方式代表記憶的三種形式:家庭相冊中個人角度的私人記憶;官方具有傾向性的歷史記憶重建;隨時籠罩著人們卻模糊不清的集體記憶。三組作品將采取三種不同的展示方式:放置在展櫃中的照片;懸掛於墻壁的油畫;以畫屏隔成的“迷宮”中的巨幅水墨畫。

在展覽目錄中,將舉例說明創作的整體過程。

EXHIBITIONS

overview of all exhibitions & Events

vernissage rathauspassage

January 11th 2016

exhibition rathauspassage

January 11th - March 16th 2016

Opening times: Mo - Sa, 10am - 7pm

Sundays by appointment (rental / events)

Rathauspassage Hamburg

Rathausmarkt 3

20095 Hamburg

Vernissage Barlach-halle K

November 9th 2016, Wednesday 7pm

exhibition in the Barlach-Halle K

November 9th – November 29th 2016

Opening times: Tue – Sun, 12pm - 6pm

Barlach Halle K

Klosterwall 13

20095 Hamburg

(only 5 minutes walking from Hamburg Main Station!)

China im Gespräch: War da was?

China erinnert sich nicht gerne an die Kulturrevolution

July 13th 2016

Hosted by the Bosch Stiftung:

Robert Bosch Stiftung GmbH

Französische Straße 32

10117 Berlin

Special exhibition Facets of Remembering: 1968 Global China and the World

September 12th - November 11th, 2018

Ethnological Museum Heidelberg

Hauptstraße 235

69117 Heidelberg

Tel: +49 6221 22067

Email: info@vkm-vpst.de

Vernissage + Exhibition in the rathauspassage

This special art project was inspired by Ni Shaofeng.

The topic will be critically examined with many guests and conversation partners. Artists from China will join, including Zhou Luwei.

Showcased in the rooms of the Rathauspassage, located below the Rathausmarkt in Hamburg.

Best to find by accessing via the subway-entrance in front of the ‘Bucerius Kunstforum’.

Date

January 11th - March 16th 2016

Opening times: Mo - Sa, 10am - 7pm

Sundays by appointment (rental / events)

(Vernissage on January 11th, 6PM)

Address

Rathauspassage Hamburg

Rathausmarkt 3

20095 Hamburg

Free Entrance!

Contact:

Tel: 040 / 36 90 09 – 7

Fax: 040 / 36 90 09 – 99

Email: rathauspassage@passage-hamburg.de

Vernissage + Exhibition in the Barlach-halle K

2016 marks the fiftieth anniversary of the beginning of the Cultural Revolution in China. For the artists Ni Shaofeng and Deng Huaidong, this is an opportunity to engage visually with the process of remembering a historical event. As a starting point, they take photos and productions produced for state propaganda that were intended to present the Cultural Revolution in an ideal light and transform them into partly large-format ink and oil paintings.

The Chinese proverb “Yanjian weishi,” which essentially means “seeing is believing,” serves as the motto of the exhibition and points to the ambiguity of the images and their messages. The artists want to encourage visitors to critically examine the visual legacy of the Cultural Revolution.

A large number of these works will be shown from November 9th to 29th, 2016 as part of Hamburg's China Time in Barlach Halle K (5 minutes from the main station):

The duo “Eva & Alice” will perform flute music from several centuries at the opening.

Date

November 9th – November 29th 2016

Opening times: Tue – Sun, 12pm - 6pm

(Vernissage on November 9th, 7pm)

Address

Barlach Halle K

Klosterwall 13

20095 Hamburg

(only 5 minutes walking from Hamburg

Main Station!)

Entrance Fee

The vernissage is free of charge for invited guests.

Regular entry: 5€

Reduced entry: 2€

Children, young people and members of the HSG have free entry.

On November 19th at 3PM the artist Shaofeng Ni will offer a guided tour of the exhibition. There is a fee of €10 (reduced €5) including entry to the exhibition.

Shi Ming

on the occasion of the exhibition opening:

20 years ago, ladies and gentlemen, 20 years ago I happened to meet a German intellectual in Aachen. We talked about the Germans and Germany. He complained and said that young Germans were fed up with constantly having to remember the Third Reich, otherwise they might not even graduate from high school... And he himself understood that the younger generation would rather look forward into the future. Why not, he asked - more to himself than to me, a stranger from China who was surprised that memories in this country could be so strong as to force an entire generation to want to get rid of these very memories?

Ten years ago in China I met a young woman from Essen, one of the younger ones who, according to that intellectual in Aachen, preferred to look forward. She told me that many Chinese people in China unpleasantly reminded her of the German shame, namely the Third Reich. “Many Chinese don’t think Hitler is that bad!” and that ashamed her. Out of necessity of having to correct her Chinese counterparts' glorified image of Germany every time, she ended up pretending that she was Swedish, she said. Since I now know that the woman never lies, the force of the memories astonishes me even more: In order not to have to look ahead, she directs it somewhere else, even calling herself someone who she is not?

Five years ago I read a book by a German historian who wondered how human memories could be so unreliable. Many stories about how the night of the bombing in Dresden went are simply wrong if you compare them with historically proven facts. Meanwhile, NPD members of the Saxon state parliament protested against forgetting the German victims of that night. Of course, they themselves refused to commemorate victims in England, for example in Coventry - the historical cause from which the Allies' act of retaliation resulted.

This time I'm no longer surprised: our human memories may traumatize us, embarrass us or make us angry. But we, whether we like it or not, can never get rid of them. Otherwise we have to deny ourselves. Otherwise, out of self-denial, we give ourselves away - demagogues of all colors, for example.

Who, ladies and gentlemen, am I telling this to? And why am I saying it? Simply because when it comes to “remembering,” we Chinese experience exactly the same tormenting ambivalences and struggles, for example with memories of the Cultural Revolution. Right at the end of the 1970s, as soon as the horror with millions of deaths was over, the Communist Party called on us to look forward to the future - towards making money! No more red ideals like the liberation of humanity. No, we should, indeed must, from now on only free ourselves from empty wallets. When I was growing up, enough Chinese people from Beijing and Shanghai dressed up and put on awkward accents to avoid being recognized as mainland Chinese - we wanted to come from Taiwan or at least Hong Kong so as not to be shamed by shadows of our past such as the Cultural Revolution.

Around 2007, instead of right-wing NPD people in Dresden, the Chinese author Zhang Chengzhi from Ningxia remembered the Cultural Revolution as his youth, which he did not regret a single bit, despite all the dead, insulted, tortured and the destruction. For whatever reasons and causalities. “Qingchun Wuhui” (No Regrets for My Youth) was the title of his memoirs.

In view of the force of memories, which a person cannot escape one way or another, and in view of the Freudian danger that transfigured and suppressed memories could drive people crazy and deform them into psychopaths - in view of this, everything is about the “remember” in which lies no difference at all between Germany and China, between Germans and Chinese?

One difference strikes me: In Germany there are - as yet - no depressing indications of a so-called repetition of history - fascism in particular - visible, even if Pegida and AfD are causing enough people in this country to be very worried. But for us Chinese, memories of the Cultural Revolution, which so many of us have tried to avoid for decades, are coming back to haunt us with every passing day. Sometimes I even suspect that I myself don't remember the ghost. That ghost may still be omnipresent.

In 2012, mass demonstrations against Japan broke out in more than 200 Chinese cities. Surging seas of red flags, loud roars of revolutionary songs, here and there someone chanted Mao quotes again, only to then drag everyone who resisted the mass mob out of their cars and beat them up. This isn't a distant memory. It is part of the Chinese present.

Since then, hundreds of thousands of people have disappeared for weeks, even months, without a trace. Nobody knows where they are or what is happening to them. At some point, official media will announce which of the disappeared will reappear as convicted criminals, branded evildoers or deposed traitors. No traumatizing memory from 1966, when the Cultural Revolution unleashed the ominous force of the Red Terror, as it was said. No, it is part of the Chinese present. Date: 2016.

Certainly, humanity should no longer liberate today's youth, as Chairman Mao once ordered. Instead, the propaganda counts years, if not days, until the Chinese nation rushes back to the top of the world and the China model shows humanity the way to all promises. The chairman who calls on us Chinese to do this has a different name now. Nevertheless, critical minds in China whisper to one another: Is the Cultural Revolution back? It seems to me: it's not back, rather it's not over yet.

Oh yes, the question has not yet been completely answered: Why am I telling you this, ladies and gentlemen? The questions about “remembering” affect us all in one form or another in one way or another. Now two artists, Ni Shaofeng and Deng Huaidong, are grappling with the same questions we are. Only that they are more creative, more artistic and they do it in form of expressive images which they call “facets of remembering”. And today these artists have invited all of us, Chinese, Germans and people from anywhere else, to join them in exploring this question about us, together as humans. I accept your invitation with a beating heart. I hope you, ladies and gentlemen, do the same.

Thank you.

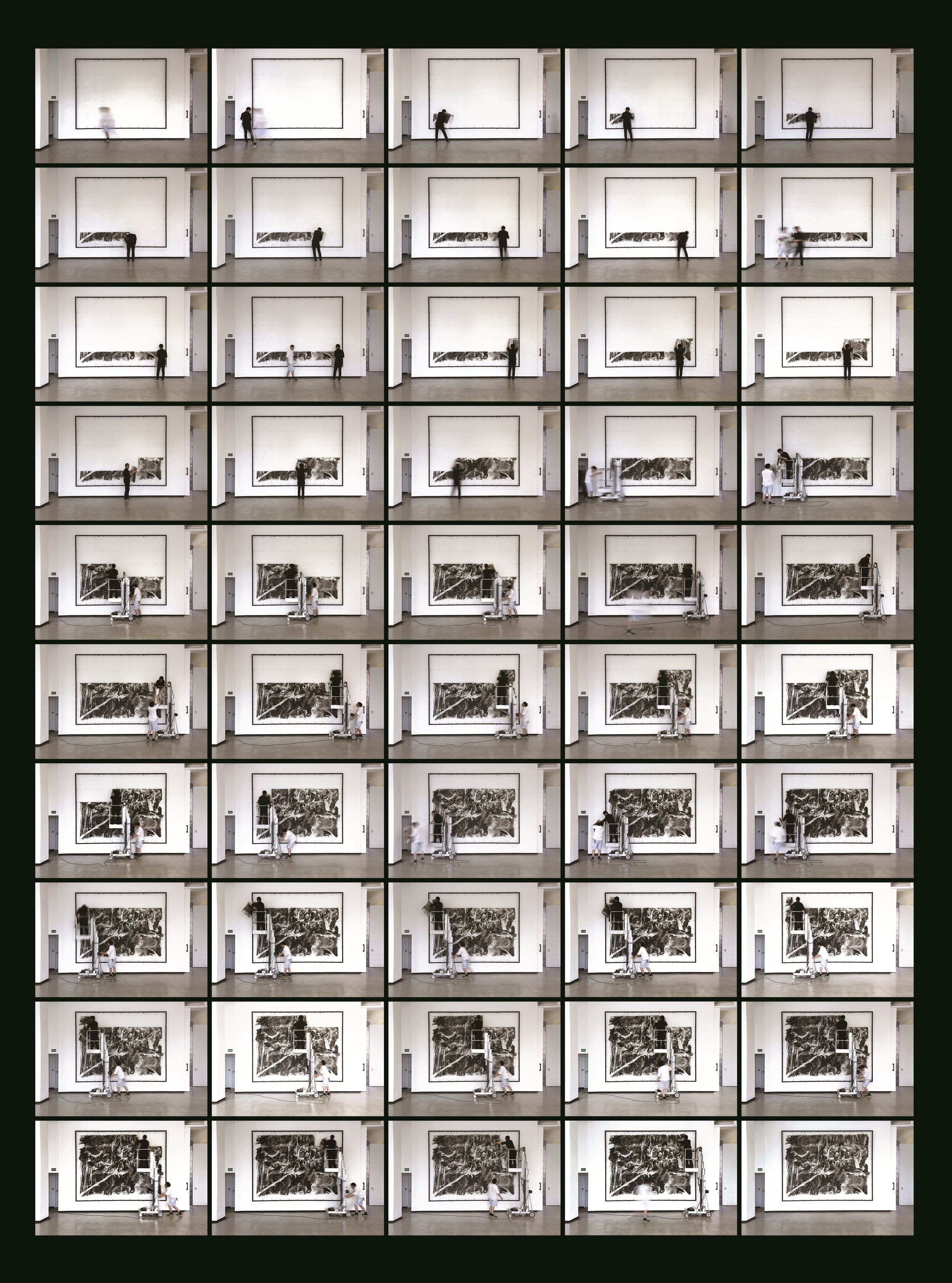

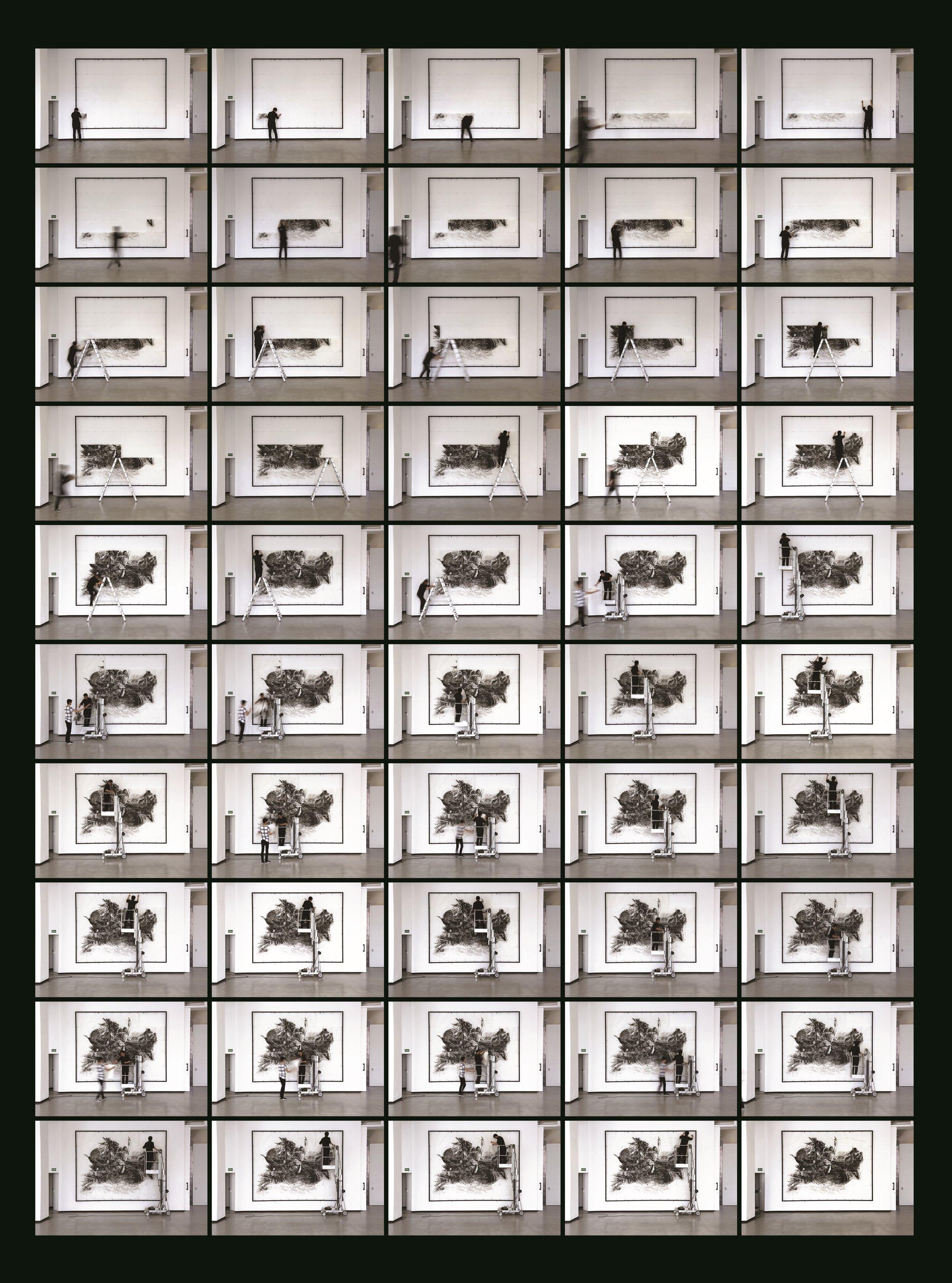

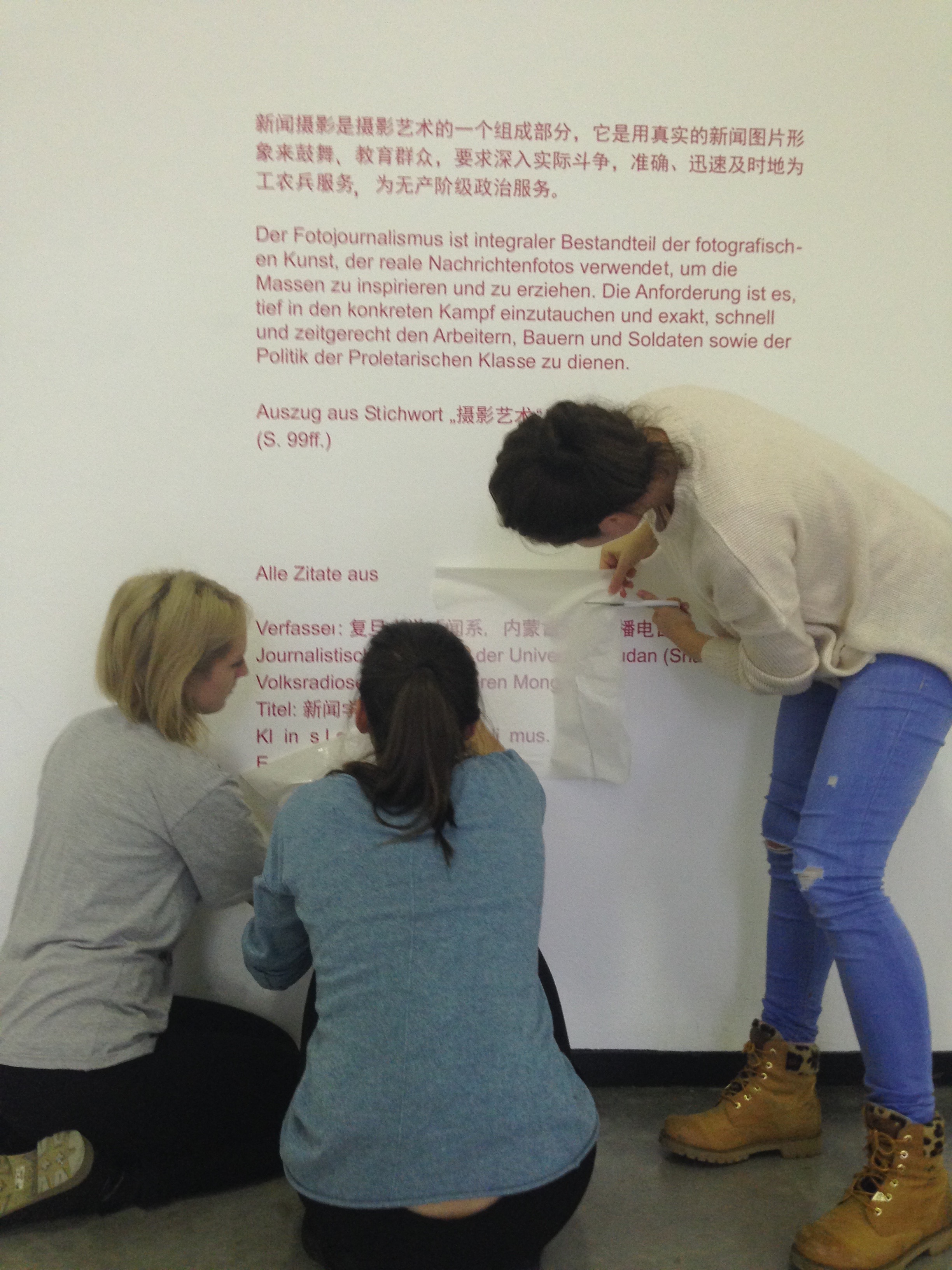

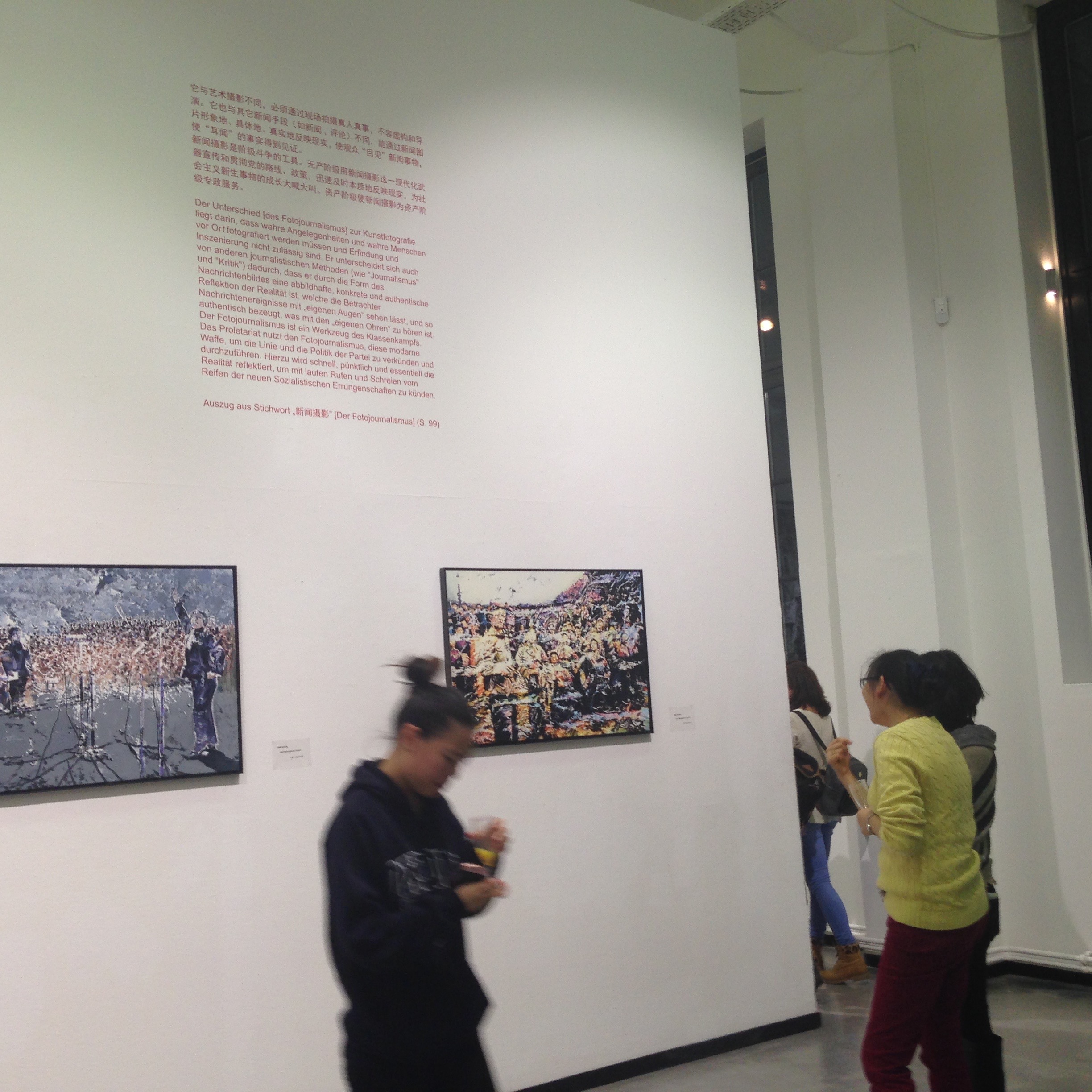

Preparations 布展现场

China im Gespräch: War da was?

China erinnert sich nicht gerne an die Kulturrevolution

Hosted by the Bosch Stiftung.

对话中国,2016年6月13日,伯林,由罗伯特·博世基金会举办

Date

July 13th 2016

Address

Hosted by the Bosch Stiftung:

Robert Bosch Stiftung GmbH

Französische Straße 32

10117 Berlin

Special exhibition Facets of Remembering: 1968 Global China and the World

记忆 – memory. Under this slogan, the two artists Ni Shaofeng and Deng Huaidong summarize their goal and motivation for this exhibition: “Facets of Remembering: 1968 Global China and the World”. On display are works that are strongly based on propaganda art in the People's Republic of China around 1968. A time in which students all over the world were protesting and Germany was in turmoil as well. The year 1968 also fell into the peak phase of the so-called “Cultural Revolution” in China, which lasted from 1966 to 1976 and is still referred to by some Chinese as the “Ten Years of Chaos”.

But there is something new about this art on display: while propaganda art from this period primarily made use of bright and radiant colors, Ni Shaofeng's ink drawings are remarkably colorless. In the largest room in the exhibition, his black and white paintings extend to the ceiling, only interrupted by portraits of the original propaganda posters cleverly inserted into the works, whose Chinese catchphrases can be found in German translation on boards in front of the picture walls. This gives the visitor a direct comparison of the model and the new work and also a better impression of the late 1960s depicted.

Even though Ni Shaofeng himself experienced the period mentioned as a small child, for him it’s not an emotional work, but rather a rational one. The idea for this exhibition came to him when he realized in 2016, on the 50th anniversary of the beginning of the “Cultural Revolution,” that none of his fellow artists had artistically processed this topic or at least made such plans. Ni Shaofeng now wants to take action against this silence with his exhibition. True to Hegel's saying, “We can learn from the history of peoples that peoples have learned nothing from history,” which he himself likes to quote, he would like to encourage visitors of his exhibition to reflect on the past instead of overlooking it and suppressing the unpleasant things. “I don’t want the young generation to ask us in 50 years: ‘What did you do?’ or not know anything about history,” he explains his motivation.

The works of Deng Huaidong, who artistically supported his former fellow student Ni Shaofeng in this project, can be found in a smaller adjoining hall of the Ethnological Museum. However, his approach is different: First he painted oil paintings in the old propaganda style, then allowed some of the paint to flake off, photographed the result and continued to fade the color on the computer. When you look at his works, it seems as if you are looking directly at our memory: past events are forgotten and become fragments, just as the color of the pictures peels off and the motif develops fault lines. The artist chose the form of photography because it is more personal to him; like looking at a photo album in your own home.

On Sunday, September 9th, 2018, the exhibition was officially opened with a concert and around 120 visitors streamed into the halls. The positive response and the conversations held among the visitors showed that both Ni Shaofeng and Deng Huaidong had achieved their goal that evening: the visitors discussed the past.

This exhibition was made possible through the collaboration of the Heidelberg Ethnological Museum, the Center for Asian and Transcultural Studies, the East Asia Department Library of Heidelberg University and the Heidelberg Confucius Institute.

© 2024 Konfuzius-Institut an der Universität Heidelberg e.V.

Date

September 12th - November 11th, 2018

Address

Ethnological Museum Heidelberg

Hauptstraße 235

69117 Heidelberg

画展目录《眼见“为实”》已经由德国东亚出版社出版发行,其中收录了著名美术史家瓦格纳教授、著名汉学家司徒汉教授及著名记者史明先生的专文,详情请见出版社网页:http://www.deutsche-ostasienstudien.de/doas/025.html

本网站的Press栏目已推出文章节选的中文译文。

selection of sketches by ni Shaofeng

A selection of sketches by NI Shaofeng can currently be seen at the MUNICIPAL CINEMA METROPOLIS.

倪少峰作品的部分草稿将在KOMMUNALES KINO METROPOLI影院同时展出。

Date

ongoing

Address

Kommunales Kino Metropolis

Kleine Theaterstraße 10

20354 Hamburg

ARTISTS

Ni Shaofeng

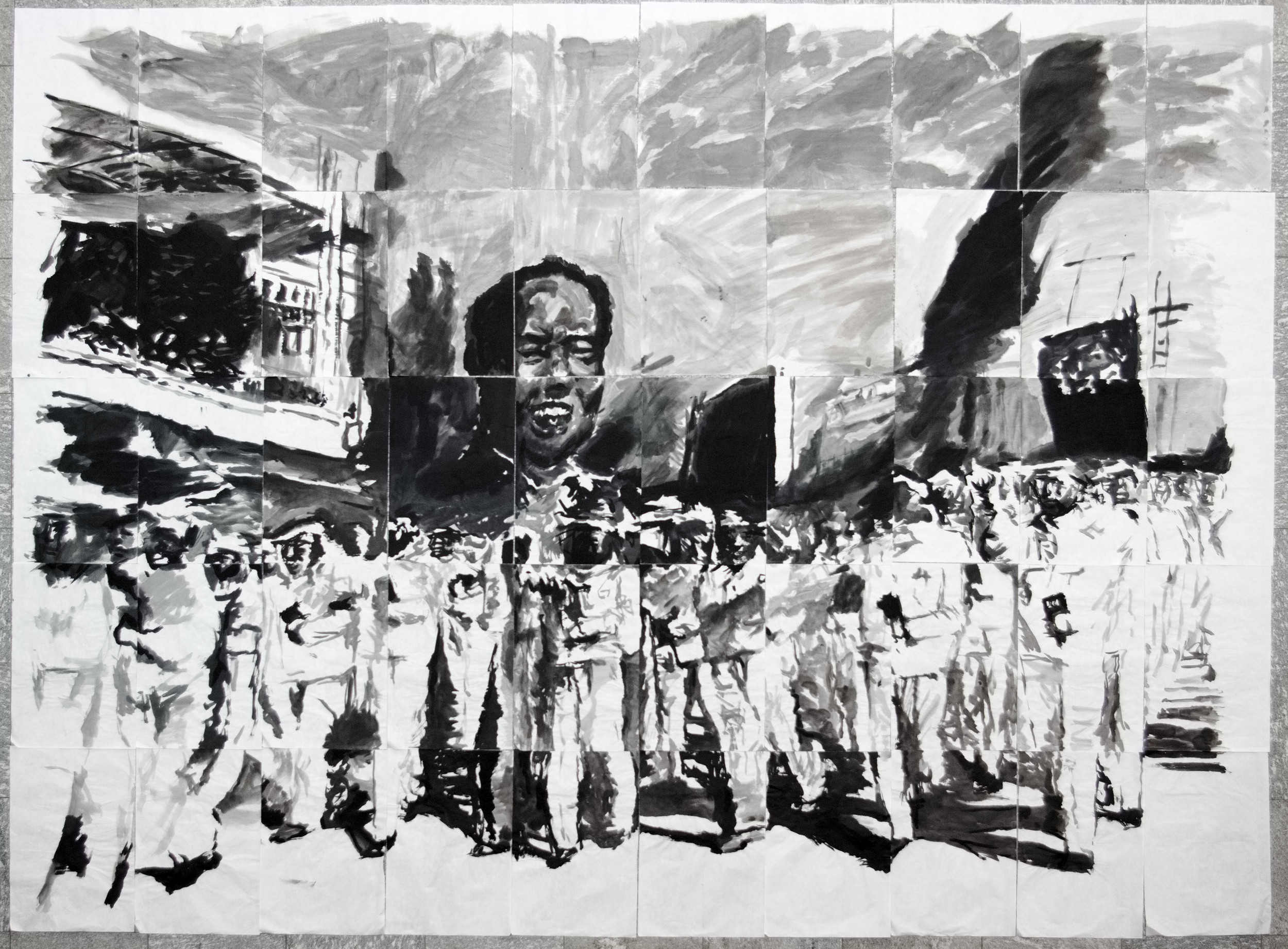

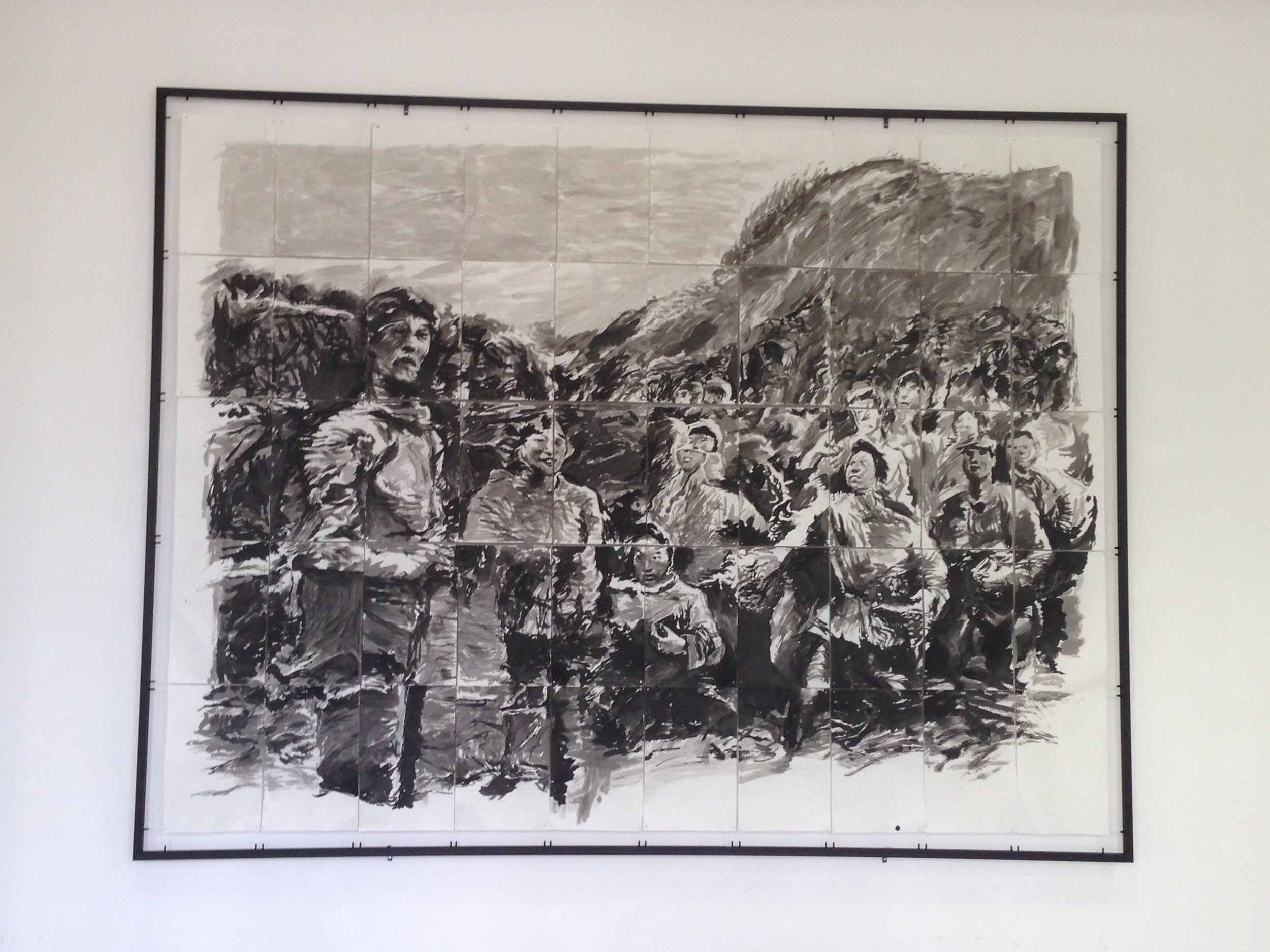

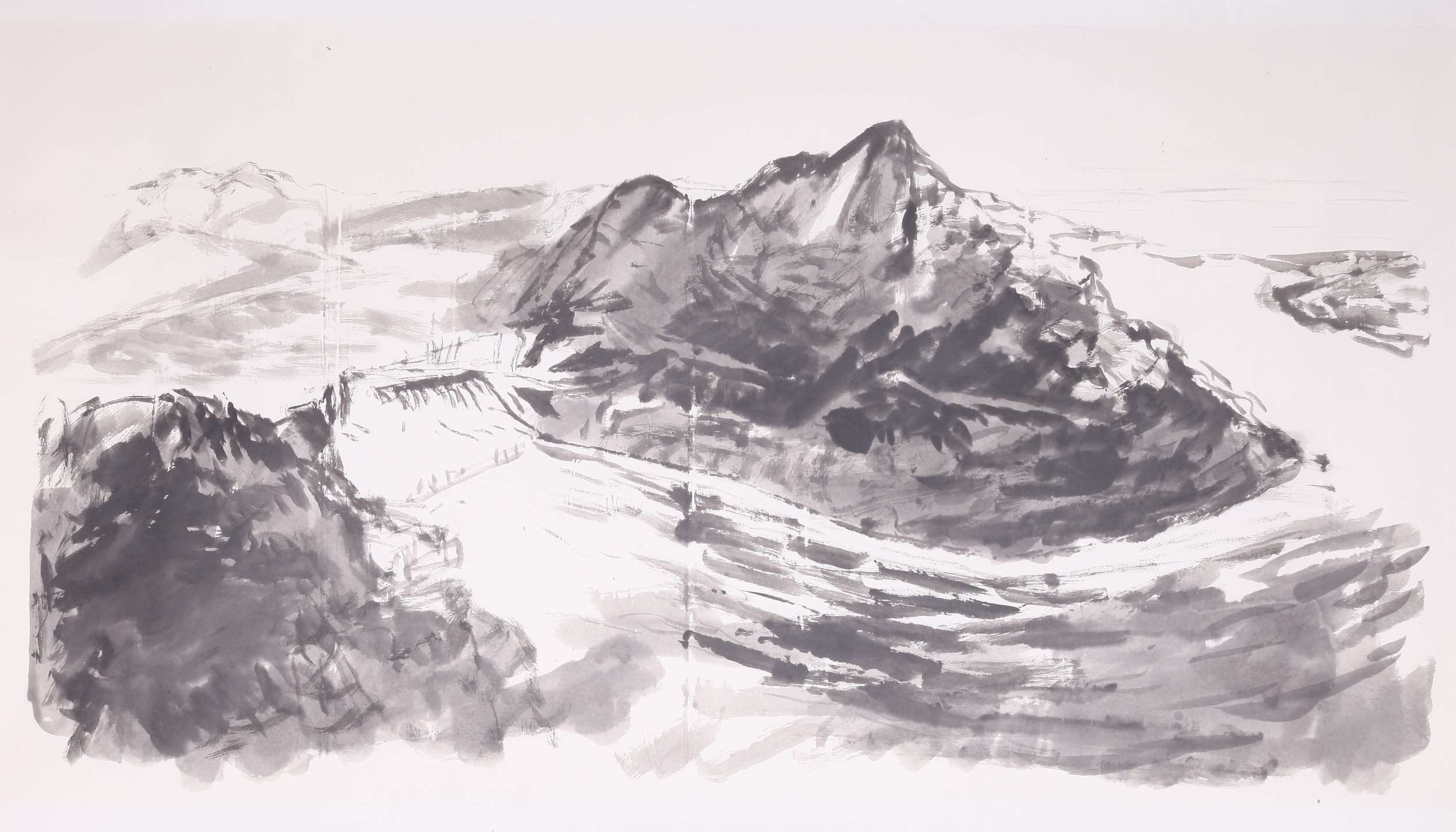

He paints the deformed motif with Chinese ink, then separate it into fifty sections. He reproduces the fragments as separate ink paintings. Recombined, they form a larger, but less detailed image of the original motif .

Er malt das verformte Motiv mit schwarzer Tusche ab. Dieses Tuschgemälde teilt er wiederum in 50 Einzelteile. Jedes Bildfragment, das dabei entsteht, überträgt er abermals auf Reispapier, diesmal jedoch in einem weit größerem Format. Die Einzelteile werden dann zu einem großen aber sehr viel gröberen Gesamtbild zusammengesetzt.

用水墨畫臨摹變形處理後的照片,然後加以分割並再次臨摹。重新拼合後形成的畫幅更為粗獷、然而變得模糊起來。

Foto: Markus Diehl Pop-Temple Hamburg

Deng Huaidong

He paints the deformed images in oil. He photographs his painting and then reduces the photo to family album size.

Er suchte den Weg zur Vergangenheit durch einen künstlerischen Prozess zu bewältigen, dessen Endprodukt scheinbar zu einem historisch Überrest der Kulturrevolution selbst wird. Er malte die Fotos der verformten Bilder und all ihre Verzerrungen und Zerstörungen mit Öl auf Leinwand in einem großen Format erneut ab. Diese Ölgemälde fotografierte er wiederrum ab. Die Fotos erhielten bei der Entwicklung der Abzüge eine grobkörnige, historisch anmutende Materialität und wurden in Schwarz-Weiß gehalten. Zudem sind sie in einem sehr kleinen Format entwickelt worden. Zusammen mit der Beschädigung und der Ausstellung in einer Vitrine bekommen sie den Charakter von historischen Artefakten.

將圖像繪制成油畫,然後進行拍照,最後縮洗為相冊尺寸大小的照片。

Wang Jinggang&Zhou Luwei

He photocopies the picture of the deformed images on a canvas and then paints a large format picture reconstructing the original motif of the photograph in the realistic style of that earlier period. (Some of the works are painted by Zhou Luwei, wo has withdrawn from this projekt.)

Er beschäftigte sich mit der Wiederherstellbarkeit von Erinnerung. Er fotokopierte die Fotos der deformierten Bilder auf eine Leinwand und malte sie anschließend farbig in Öl nach. Mit der Ölfarbe ergänzte er Bilddetails aus der Erinnerung, verdichtete sie und reparierte die deformierten Partien. Am Ende entstand wieder ein heiles Propagandabild im Stil sozialistischer Ölmalerei unter dessen Oberfläche ein ganz anderes, verformtes Abbild der Vergangenheit verborgen liegt. (Einige Werke stammen von Zhou Luwei.)

將放大處理後的照片復印在畫布上,並將變形後的圖像復原為當年寫實風格

的油畫 。(部分作品为周鲁伟所作)

PRESS

Catalog to the Project under the Same Title

Zu diesem Anlass ist unter dem gleichen Titel auch ein Katalog erscheinen

画展目录《眼见“为实”》已正式出版发行

其中莫妮卡·瓦格纳教授专文《致力于图像改造》的译文刊载如下:

致力于图像反思与改造

莫妮卡·瓦格纳 (Monika Wagner)

在欧洲,一提到“文革”,人们想到的多是宣传图片,整齐队列中欢快的群众,在颇具气势的透视关系中得以呈现。穿着蓝色工装的幸福的工人集体;身着绿色军装,姿态夸张的坚定战士;无所不在的政治领袖,时而正装,时而军装,或掩映在红旗的海洋,或出现在红宝书的封面。鲜红的颜色,构成“文革”宣传图片的基调。1966—1976这十年曾经被称作“红色岁月”。用红色服务于政治,可追朔到国际共产运动,以及来自布尔什维克的“红色卫队”和“红军”。 “红”在俄语中有“美”的意思。而在中国传统文化中,“红”是吉祥之色,也绝非巧合。“文革”图片宣传(包括摄影印刷品)通常明亮而鲜艳,用红色将共产主义颂扬为一个幸福的新时代,也就是顺理成章的了。同时,许多至今仍旧无名的摄影师,使用了1920年代在“新视野”便已被普遍采用的艺术手法:俯视与仰视、大场面广角镜头、动态对角构图等。早在苏联建国初期,这类图像模式便已被赋予强烈的政治色彩,成为进步信仰的象征。在这批针对图像宣传的作品中,倪少锋与邓怀东的处理手法虽有所不同,但其目的都在于促进对“红色岁月”的思索与反思。目前,这类反思仍处于刚刚起步阶段。两位艺术家在“眼见‘为实’”联展中,只是间接地涉及到“文革”的政治方面。他们着眼点在于更为棘手的“文革”图片宣传。作为发动群众运动的重要手段,图片宣传弥漫于生活的方方面面,影响了日常生活的行为方式。倪、邓两位艺术家在他们的画作中,彰显了如下认识与创作的初衷:“文革”图像从未彻底隐退,依存活在人们的脑海中。鉴于目前的中国时局,如仍不加以反思,仍沉溺于怀旧情愫,这类图片迟早会卷土重来。

在“眼见‘为实’”联展作品中,画家采纳原始照片中的动态构图及慷慨激昂的姿势,而图片宣传以其固有的特质却被赋予新的内容。(图1、2)

图 1

图 2

同时,他们通过绘画语言与媒介,对宣传图片加以改造,实施解构。将当年被大量复制的宣传照片转化为单件手绘作品。这样以来,倪少峰、邓怀东的创作也就并非构成与文革图片对立或相左的作品,而是对原来图像“样板”的视觉评述,其表现也更为细腻、微妙。他们是透过媒介的转换,来表明自己的观点与态度的——无论是从摄影转换为中国水墨画,还是从摄影转换为起源于西方的现代油画。

......

图像的再教育

倪少峰采用与邓不同的画法,无论原来的照片是黑白或是彩色,他均用白纸黑墨。宣传画无论怎样鲜艳,也要接受画家的“再教育”,也就是说,通过媒介转换使其纳入中国的绘画传统语汇体系之中。他对照片图像的重新阐释,他那笔走龙蛇的挥洒,与其说是再现了渐渐淡去的记忆,不如说是让新的作品重新汇入水墨画的传统的长河。

图 3

照片复制品经由传统绘画技法转化为个人的笔法,人物的意义也随之产生变异。首先,我们注意到,当色彩退去,尤其是“革命红”消失,画面的语义发生了转换。色彩不再,最具影响力的感情诉求手段之一也就退出了画面。例如,登上山头专心学习语录的那组男性头顶上迎风飘扬的红旗,在倪少峰的水墨画中变为疲倦乏力的灰色碎片(图4、5)。周围的群山在近乎狂舞的书法线条中与之浑然一体(图6),这让人联想到传统的云图(图3)。笔法的运用与黑白颜色很大程度上有助于具体对象的抽象化处理,加强了与传统书法的关联。

图4

图 5

图 6

不仅限于色彩,画家对画面中的人物,也实施干预与变异,这一点远观几乎无法察觉。但逼近画面观摩,便可见到用笔着墨的轻重缓急,发现原有构图的化解与重组,这甚至体现在步调一致的游行队伍里(图7、8)以及同属宣传机器的样板戏的场景之中。

图 7

图 8

落笔运笔之间,视觉可感受到的起承转合,墨色的浓淡聚散,直接介入人物形象的处理。使之不再确定,令其断裂,甚至身首两异(图9)。动态宣传照片场景中的主要人物,在媒介的转换过程中似乎遭遇了不测,这些人物的躯体不复完好。鉴于干预和伤害是经由绘画手段实现的,因此作品的解读呈现开放性,需要观者不断参与和发掘,以探究其潜力。

图 9

此外,在绘画技巧方面,还有一点也值得称赞。倪少峰的巨幅作品由50个单幅构成(图10)。画幅经过叠加,成为375 x 460厘米的巨制,如同“文革”中的宣传墙壁,其对象是公共空间里的大众。每一画幅为国画大三尺中的一尺,宣纸的吸墨性能良好,这样就可以看出落笔行笔各种不同的走势。一张张画幅逐次排开,构成巨幅网状作品。这里运用传统手工放大的拷贝技术。影院电影广告海报画家曾使用过这种技术,他们将照片或电影镜头放大,来为公共空间绘制巨幅招贴画。不过,即便是黑白电影一般也会绘成彩色招贴。倪少峰有意呈现网格放大的技术环节,五十张画幅并未链接得毫无缝隙、宛若一体,而是保持一定的间距,以便让观者可以看出网状结构这一构造性原则(图11)。

图 10

图 11

这样的作法,其目的在于,表明绘画作品源自历史摄影原型,并非虚构的图像。此外,网格并未做精准衔接,而是透露出些许的重叠、重复、延伸或缩短。这很像大型电影海报,由贴画工人在公众空间覆墙时出现的情形。当切线,似乎不经意间,剖切过面部、眼部、嘴部,或将臂膀截断的时候,效果尤其引人注目(图12)。再者,巨幅画作的悬挂方式使其在空气运动中微微波动,引起向外部空间开放的视觉效果。这一切,导致了陌生,产生了化腐为奇的独特效果:“文革”的图像宣传接受了改造。

图 12

绘出岁月留痕

不同于倪少锋的水墨画,邓怀东在其《眼见“为实”》展出作品中采用了彩色油画的形式。然而,他选用的色系与所选用的文革彩照差距甚大。例如,在那副正面像中,毛泽东右手采用了典型领袖挥手的姿势,而左手握在一个与观众产生距离的栏杆上,军装的绿色呈现出异样的苍白(图13、14)。红卫兵袖章与红五星历历在目,而红领巾却模糊难辨。与照片相比,油画似乎褪色,不再光彩夺目。

图 13

图 14

此外,画面给人以被褶皱过的印象,并与所描绘的主题相脱离,显得颇为异样。因此,在《毛:正面像》一画中,很难确定何处为中山装皱纹,何处为背景纸张褶皱。在描绘胸前紧握红宝书的天安门广场士兵的那幅画上(图15),画面本身似乎已风化剥落。

图 15

毛主席语录依旧红光闪烁,而画面从上部起的某些部位,似乎已经脱落,露出下面的墙体(图 16)。邓的画作暗示,这些是文革招贴,是过往时代残存的遗物。物转星移,画面仿佛褶皱、破碎、龟裂。它们已经变得苍老。这令人连想到在欧洲上个世纪60年代的“招贴撕剥”作品,而当时这种碎裂美学专注于产品推广和刺激的颜色。颜色,这一生命的象征,在邓的作品中失去了光泽,却未全然散去。画面上憧憧之影,游离在阴阳两界之间。如同倪的作品,在邓的作品中手工制作过程至关重要。作品基于文革历史照片,经过转拍复制,然后粘贴敷墙。墙体的纹路便被拓印下来,显出砖体、石面、灰墙等不同机理。在某些部位,故意将图片杂乱地贴在墙面上,以使纸张褶皱移位。这样,画面图像就产生如同刮旧复用的羊皮纸卷般的变异:纸张与图像均受到磨损,现出岁月留痕。

图 16

艺术家对敷墙后的照片进行再次拍摄,这样室外光线,褶皱边沿,过度曝光都会造成画面的变异。几经转换之后,画家才进入最后的手工绘制。例如,在《忠字舞》一画中,慷慨激扬高举双臂的红卫兵与砖体墙壁重叠融合,浑然一体(图 17)。

图 17

这里,原始照片在与图像的渗透中已经很难辨认出来,同时其新的面貌却又清晰可见。解读或许关涉到观者的文化的背景。高举的双臂的“激情形式”、砖墙、红卫兵褴褛的军装、人物的被吞噬,至少在具有欧洲文化背景的观者看来,表现了受害者的屈从与无助,让人不由地联想到戈雅作品中五月三日抢杀的情景(图18),而不再是欢快的舞蹈。

图 18

精湛的油画技术造成的逼真感给人以画面和砖墙融合的印象。整个情形颇有些追魂摄魄的效果,尤其是因为这幅作品破例使用了黑白照片作为样本 (图19)。这在投影般的色彩和形体的平面化倾向中显现出来。当美国艺术家西蒙·阿提1992年将二战时犹太人生活私人黑白照片投射在柏林的军械库区(大屠杀前犹太人聚居地)房子的墙壁上,所产生的人物与地点融合的效果颇为类似(图20)。

图 20

区别在于:西蒙·阿提通过日常生活照,包括纳粹丑化犹太人的照片,使墙面鬼影幢幢,让街道再次热闹起来,他诉说的是对犹太人集体屠杀的暴行;邓怀东的描绘革命宣传中领袖以及群众的作品,指向的却是尚未反思的,被边缘化的,然而留存在集体记忆中积淀下来的图像知识。

为了掘进到历史的沉积的深层,倪和邓的这一《眼见“为实”》艺术项目,不仅唤醒了人们对那曾经风云一时的图片的记忆,同时也对其进行了批判性分析并且提出了质疑。他们的作品超越了销路颇佳的“毛时代政治波普”,对文革图像的反思与改造自此发轫。

(完)

翻译:云峰

德国之声:半世纪后 文革黑暗面在中国仍是禁忌

(柏林墨卡托中国研究中心 Mercator Institute for China Studies 座谈会,艺术家倪少锋作为主讲人之一参加座谈)

http://www.dw.com/zh/半世纪后-文革黑暗面在中国仍是禁忌/a-19257663

Der Tagesspiegel: Die Kulturrevolution in China Zurück zu Mao?

http://www.tagesspiegel.de/politik/die-kulturrevolution-in-china-zurueck-zu-mao/13596648.html

Monika Wagner, Professorin für Kunstgeschichte der Universität Hamburg anläßlich der Ausstellungseröffnung:

Die drei an dieser Ausstellung beteiligten Künstler, Ni, Shaofeng, Deng Huaidong und Zhou Luwei haben alle drei in den frühen 1980er Jahren, also kurze Zeit nach Maos Tod und dem Ende der Kulturrevolution 1976 und der nachfolgenden moderaten Liberalisierung an der Pädagogischen Hochschule Shandong in Jinan MALEREI studiert.

Alle drei nehmen in ihren künstlerischen Arbeiten direkt auf konkrete Vorlagen der Bildpropaganda der Kulturrevolution Bezug. Alle drei tun dies, indem sie die Motive und die stilistischen Eigenheiten einerseits aufrufen und andererseits zugleich durch Stilmittel und Verfahrenstechniken konterkarieren.

Das heißt, die drei Künstler malen keine Gegenbilder oder Alternativen zu dem pathetischen, expressiven Bildvokabular der Kulturrevolution. Ihr Kommentar ist subtiler. Sie transferieren das Ausgangsmaterial - in der Regel eine drucktechnisch vervielfältigte Fotografie - in ein manuell hergestelltes Bild. Wie dies geschieht, darin liegt der Kommentar zum Vor-Bild.

. . .

Ni Shaofeng, der Initiator der Ausstellung transferiert die Bildpropaganda in den Duktus tradierter chinesischer Tuschmalerei auf dem entsprechenden Papier. In der Raschheit der Geste werden die arretierten Posen der Vorlagen verflüssigt und zugleich neu konstituiert. Denn der Rhythmus der Pinselzüge, des Neuansetzens und des Ausstreichens der Tusche greifen in die Figuren ein, lassen sie stolpern oder auch mal zerbrechen, verletzen oder köpfen sie. Doch indem diese Eingriffe gewissermaßen der Maltechnik zuzukommen scheinen, bleibt der Kommentar offen und muß durch Sehen erschlossen werden.

Monica Wagner, Art History Professor of the University of Hamburg, at the opening of the exposition:

All three participating artists – Ni Shaofeng, Deng Huaidong and Zhoug Luwei – were Art students, specialising in painting at the University of Education Shandong in Jinan in the early 1980s. At that time, Mao’s death was fairly recent and the cultural revolution of 1976 had already ended, followed by a moderate liberalisation.

All three, through their works of art, make reference to specific patterns found in pictures used for propaganda during the Cultural Revolution. In order to do this, they recall motives and stylistic singularities of the model on the one hand while offering a contrast depicted in stylistic devices and methodical techniques on the other.

This means that the artists’ works are not alternative paintings made to counter the histrionic message expressed throughout the collection of pictures used in the Cultural Revolution. Their response is subtler. They transfigure the original material, which is a typographically reproduced photograph, into a manufactured painting. And the way they do this reflects their response to the original picture.

…

Ni Shaofeng, initiator of the exposition, reworks the propaganda pictures using ink painting on adequate paper, a characteristic style of traditional Chinese painting. In a swift gesture the still poses of the original paintings are liquefied and, at the same time, newly constituted. The rhythm of each brushstroke, the rearrangement and the spread of ink interfere with the figures, make them stumble or even break down; they violate and decapitate them. And yet, the fact that those interventions seem to be part of a painting technique is the reason why the response remains open to interpretation and only onlookers will be able to determine it.

(translated by Cerise Lai-Magalhaes)

http://www.abendblatt.de/hamburg-tipps/article206916895/Das-grosse-Trauma-der-chinesischen-Zeitgeschichte.htmlAusstellungs-Tipp

Das große Trauma der chinesischen Zeitgeschichte

Von Matthias Gretzschel

Was sich vor ziemlich genau 50 Jahren in China zusammenbraute, war in Wahrheit keine Revolution, sondern ein barbarischer Akt der Vernichtung. 1966 zettelte Mao Tse-tung die sogenannte "Große Proletarische Kulturrevolution" an, die einem einzigen Ziel diente: Sie sollte seine Machtposition im kommunistischen Apparat sichern. Dass sie Millionen Menschen das Leben kostete und zu einer unvorstellbaren Vernichtung von Kulturgütern führte, war ausdrücklich gewollt. Mit dem von Mao propagierten "Schlag gegen die Vier Alten" waren die alten Ideen, die alte Kultur, die alten Bräuche und die alten Gewohnheiten gemeint. Alles Alte sollte zerstört werden, denn nur so könne Neues entstehen, war die kranke Idee, die Mao propagierte. Die Parolen des Parteiführers, die im "Roten Buch" zusammengefasst sind, musste jeder Chinese nicht nur bei sich tragen, sondern auch auswendig zitieren können. Die Jungen wurden gegen die Alten aufgehetzt, die Arbeiter gegen die Intellektuellen, die Bauern gegen die Künstler, Macht stand gegen Geist.

"Es ist das größte Trauma der jüngeren chinesischen Geschichte. Die Kulturrevolution konnte bis heute nicht aufgearbeitet werden, sondern wird weitgehend totgeschwiegen", sagt der Künstler und Wissenschaftler Shaofeng Ni, der jetzt in Hamburg ein Kunstprojekt zum Thema "50 Jahre Kulturrevolution" initiiert hat. Eigentlich, meint Ni, müsste die Ausstellung in China gezeigt werden, nur sei das aus politischen Gründen nicht möglich. Dabei geht es ihm mit dem Projekt "Das Erinnern – Das Entsinnen" in der Rathauspassage gar nicht vordergründig um Politik, sondern um eine künstlerische Auseinandersetzung.

Gemeinsam mit den in China tätigen Künstlern Zhou Luwei und Deng Huaidong hat Shaofeng Ni eine Ausstellung konzipiert, die von historischen Bilddokumenten ausgeht und diese auf kreative Weise verändert. "Wenn es um Erinnerung geht, sind Bilder besonders wichtig, da sie damals als Propagandamittel eingesetzt wurden", sagt Shaofeng Ni, der für das Projekt 50 historische Fotografien ausgewählt hat. Die drei beteiligten Künstler haben diese in unterschiedlicher Weise bearbeitet.

So wurden die Fotografien als vergrößerte Kopien an eine Mauer geklebt und dabei verformt, dann erneut fotografiert, als Fotoalbum-Motiv verkleinert oder in großformatige Tuschgemälde transformiert. Das Übertragen der Bilder auf eine Mauer bezieht sich auf die "Wandzeitungen", die ab 1966 überall in China auftauchten und zum wichtigsten ideologischen Kampfmittel der Kulturrevolution wurden. Die Bilder zeigen fanatisierte Menschen, die ganz in der Menge aufgingen. Zu sehen sind die politischen Führer, aber auch die uniformierte Masse der "Roten Garden", die mit unvorstellbarer Grausamkeit gegen alles vorgingen, was ihnen als "reaktionär" erschien. "Indem meine Kollegen Zhou Luwei, Deng Huaidong und ich diese Fotografien verfremden, erinnern wir an das historische Geschehen, setzen uns aber zugleich in einer Weise künstlerisch auseinander, die man als Wiederaneignung und Reflexion verstehen kann", sagt Shaofeng Ni, der als Lektor an der China-Abteilung der Universität Hamburg tätig ist.

Das Erinnern – Das Entsinnen Ein Kunstprojekt zu 50 Jahre "Kulturrevolution", Do 14.1., 10 bis 19 Uhr, Hamburger Rathauspassage, nter dem Rathausmarkt, Eintritt frei; die Ausstellung läuft bis zum 12. 2., montags bis sonnabends von 10 bis 19 Uhr

Quellenangabe: Hamburger Abendblatt Mittwoch, 13. Januar 2016